Massage is the mechanical working of muscles and connective tissues to enhance function, and to improve upon the quality and timing of the healing process. Because massage also promotes relaxation and well-being, it also has pleasurable connotations.

Myotherapy is often used synonymously for massage therapy. Myotherapy is the terminology used by many healthcare professionals because it is considered to be a form of manual medicine used for the treatment and management of musculoskeletal pain. The primary purpose of myotherapy is therapeutic. Myotherapy is designed to achieve a specific change in tissues to benefit aspects of the pathophysiological process.

A recent search of the National Library of Medicine using PubMed (May 13, 1012) using the key word “massage” pulled up 10,357 citations, 172 of which were dated in 2012. In contrast, the key word “myotherapy” pulled up 27 citations.

For decades, a vocal advocate of myotherapy was United Kingdom orthopedic surgeon Sir James Cyriax, MD (d. 1985, age 80 years). Dr. Cyriax authored three medical texts that advocated myotherapy:

Textbook of Orthopaedic Medicine, Diagnosis of Soft Tissue Lesions

Bailliere Tindall, Volume 1, eighth edition, 1982. (1)

Textbook of Orthopaedic Medicine, Treatment by Manipulation, Massage, and Injection

Bailliere Tindall, Volume 2, tenth edition, 1982. (2)

Illustrated Manual of Orthopaedic Medicine

Butterworths, 1983. (3)

In these references, Dr. Cyriax notes that harmful infections create tissue destruction, resulting in inflammation. Our body recognizes this inflammation and attempts to “wall off” the infectious pathogens by creating a fibrous response. Cyriax states (1):

“The excessive reaction of tissues to an injury is conditioned by the overriding needs of a process designed to limit bacterial invasion. If there is to be only one pattern of response, it must be suited to the graver of the two possible traumas. However, elaborate preparation for preventing the spread of bacteria is not only pointless after an aseptic injury, but is so excessive as to prove harmful in itself. The principle on which the treatment of post-traumatic inflammation is based is that the reaction of the body to an injury unaccompanied by infection is always too great.”

In their 1983 text pertaining to sports medicine, Steven Roy and Richard Irvin state (4):

“It is important to realize that the body’s initial reaction to an injury is similar to its reaction to an infection. The reaction is termed inflammation and may manifest macroscopically (such as after an acute injury) or at a microscopic level, with the latter occurring particularly in chronic overuse conditions.”

In their 1992 book titled Wound Healing (5), physician I. Kelman Cohen and associates note:

“There are two important consequences of being a warm-blooded animal. One is that body fluids make optimal culture media for bacteria. It is to the animal’s advantage, therefore, to heal wounds with alacrity in order to reduce chances of infection.”

“The prompt development of granulation tissue forecasts the repair of the interrupted dermal tissue to produce a scar.” In addition to providing tensile strength, scars are believed to be a barrier to infectious migration.

This is in agreement with the pathology text by Dr. William Boyd (6), which states:

“The inflammatory reaction tends to prevent the dissemination of infection. Speaking generally, the more intense the reaction, the more likely the infection to be localized.”

Physiologist and physician Arthur Guyton (7) adds additional support stating:

“One of the first results of inflammation is to ‘wall off’ the area of injury from the remaining tissues. This walling-off process delays the spread of bacteria or toxic products.”

The reference text, Robbins Pathologic Basis of Disease (8), makes these points:

“Inflammation is best defined as the reaction of vascularized living tissue to local injury.”

“The inflammatory response is closely intertwined with the process of repair.”

Inflammation serves to destroy, dilute, or wall off the injurious agent, and sets into motion a series of events that heal and reconstitute the damaged tissue as best as possible.

Repair begins during the early phases of inflammation. During repair, the injured tissue is replaced by regeneration of native parenchymal cells, and by filling of the defect with fibroblastic scar tissue (scarring).

“Humans owe to inflammation and repair their ability to contain injuries and heal defects.

Without inflammation, infections would go unchecked and wounds would never heal.

“However, inflammation and repair may be potentially harmful.”

“Reparative efforts may lead to disfiguring scars or fibrous bands that cause intestinal obstruction or limit the mobility of joints.”

In their 2004 book on pathology titled Cells, Tissues, and Disease: Principles of General Pathology, Guido Manjo, MD and Isabelle Joris, PhD, make these points (9):

“Inflammation is one of the basic processes in general pathology.”

“Inflammation is primarily an antibacterial phenomenon.”

“Inflammation operates against all invaders, including viruses, worms, fungi, and other parasites.”

“Inflammation is also triggered aseptically by injured tissues.”

“There can be inflammation without infection; remember that inflammation is triggered by products of tissue injury, thus any aseptic injury will trigger inflammation.”

“Because local injury is part of everyday life, inflammation is probably the most common aspect of tissue pathology and has always been perceived as a central issue in the practice of medicine.”

“Today we know that inflammation is a life-saving reaction, usually against infection.”

“Solid masses or sheets of fibrin are often seen on an inflamed surface.”

“With the microscope, some fibrin is found in nearly all acutely inflamed tissues, but an exudate is called fibrinous when fibrin deposition is the dominant feature.”

Chronic inflammation causes increasing “collateral damage.”

“Inflammation takes place in the connective tissues.”

“After a day or two of acute inflammation, the connective tissue—in which the inflammatory reaction is unfolding—begins to react, producing more fibroblasts, more capillaries, more cells—more tissue. In other words, granulation tissue arises from normal connective tissue, but it cannot be mistaken for normal connective tissue, because its fibroblasts are plumb and activated.”

“Fibrosis means an excess of fibrous connective tissue. It implies an excess of collagen fibers, with a varying mixture of other matrix components. It can be a local phenomenon, as an end result of chronic inflammation and of wound healing.”

“When fibrosis develops in the course of inflammation it may contribute to the healing process.” “By contrast, an excessive or inappropriate stimulus can produce severe fibrosis and impair function.”

Fibrotic tissue “consists of cells and fibers, with few vessels; and it tends to contract very slowly, over weeks and months or longer.”

“’Fibrotic’ collagen is characterized by excess of hydroxylation and cross-linking.”

“Why does fibrosis develop? In most cases the beginning clearly involves chronic inflammation. Fibrosis is largely secondary to inflammation.”

The interpretation is, that in a world prior to the availability of antibiotics, inflammation, with reactive walling-off fibrosis to contain pathogens, is desirable because it increases survivability of the host.

As explained by Cyriax, Roy/Irvin, Cohen, Boyd, Guyton, Robbins, and Manjo above, the trigger to the walling-off fibrosis response of the body is inflammation. Problems arise when the inflammatory trigger is non-infectious inflammation. In such cases, excessive tissue fibrosis creates local impairments in biomechanical function. This impairment in local biomechanical function affects performance, can generate pain, and accelerate degenerative changes. These impairments can adversely affect the patient for years or even decades.

A primary goal of myotherapy is to use appropriately applied mechanical forces to reverse the adverse biomechanical function of fibrotic tissue changes. When successful, that patient often experiences reduced pain, improved performance, and reduced joint stresses.

The chronic nature of this scar tissue or fibrosis is expressed in the 1998 article by Thomas Melham and associates (10). These authors note that post-traumatic scar tissue can cause pain with activity, pain on palpation, decreased range of motion, and loss of function, and that these problems are resistant to surgery and to conventional physical therapy. Excessive scar tissue contributes to chronic soft tissue dysfunction that cause significant disabilities and time lost from work or training activities, and these problems are often difficult to successfully treat. The authors discuss the mechanical and neurological adverseness caused by connective tissue fibrosis, noting:

“Many athletes develop excessive connective tissue fibrosis (scar tissue) or poorly organized scar tissue in and around muscles, tendons, ligaments, joints, and myofascial planes as a result of acute trauma, recurrent microtrauma, immobilization, or as a complication of surgical intervention.”

“This can lead to soft tissue adhesions, tendonitis, tendonosis, fascial restrictions, and chronic inflammation or dysfunction which in many cases responds poorly to conventional treatments.”

These descriptions of the mechanical pathoanatomy of the soft tissue scar/fibrosis repair process suggests that appropriately applied myotherapy would hold biological plausibility in their management. Additional support from Cyriax includes (1):

“When pain is due to bacterial inflammation, Hilton’s advocacy of rest remains unchallenged and is today one of the main principles of medical treatment. When, however somatic pain is caused by inflammation due to trauma, his ideas require modification. When non-bacterial inflammation attacks the soft tissues that move, treatment by rest has been found to result in chronic disability later, although the symptoms may temporarily diminish. Hence, during the present century, treatment by rest has given way to therapeutic movement in many soft tissue lesions. Movement may be applied in various ways: the three main categories are:

(a) active and resistive exercises:

(b) passive, especially forced movement: and

(c) deep massage.”

Here, Cyriax’s “deep massage” is equivalent to contemporary myotherapy.

The discussion and references above support the concept that adverse pathogens cause tissue destruction and subsequent inflammation. The body evolved in a manner to wall-off the area of inflammation by over healing the region with a fibrous response. The fibrous response became a physical barrier, reducing the ability of the pathogens to spread to other regions of the body, thereby improving the host’s chances for survival.

However, when inflammation is caused by non-infectious mechanisms, the same fibrotic tissue response occurs. In such cases, without infectious pathogens, the fibrotic tissue response is excessive, resulting in mechanical harm to the host. This harmful tissue fibrosis is worsened with early immobilization of the affected tissues. This tissue fibrosis is minimized with early persistent controlled mobilization.

Traditionally, myotherapy targets the mechanical adverse fibrotic tissues located in muscles and in non-contractile soft tissue (tendon, fascia, ligament, etc.) fibrosis responds best to manually applied tissue friction.

Most patients have a combination of tissues that are adversely affected by reparative soft tissue scar/fibrosis, depending on the mechanism of injury or stress. Consequently, myotherapy is often applied in combination with other adjuncts that are similarly designed to remodel and improve soft tissue scar fibrosis. An example would include joint adjusting (specific directional manipulation) to influence periarticular soft tissues. Additionally, resistive effort and range-of-motion exercises enhance the remodeling process and help to reduce chances of any degraded/remodeled scar/fibrotic tissue for reoccurring.

From Cyriax J and Cyriax P, Illustrated Manual of Orthopaedic Medicine, Butterworths, 1983 (3).

Recently (February 2012), evidence has emerged showing the mechanisms whereby massage/myotherapy influences (improves) the physiology of acute muscle injury. Investigators from McMasters University, Ontario, Canada, published their findings in the journal Science Translational Medicine in an article titled (11):

Massage Therapy Attenuates Inflammatory

Signaling After Exercise-Induced Muscle Damage

In this study, the authors note that massage therapy is commonly used during physical rehabilitation of skeletal muscle to ameliorate pain and promote recovery from injury. Although there is evidence that massage may relieve pain in injured muscle, how massage affects cellular function remains unknown.

The authors administered either massage therapy or no treatment to the quadriceps of 11 young male participants after exercise induced muscle damage. Muscle biopsies were obtained from the quadriceps muscles of these young men (vastus lateralis) immediately after completing strenuous fatiguing exercise. In the massage group, muscle biopsies were again taken immediately after 10 min of massage/myotherapy treatment; and then again after a 2.5-hour period of recovery. Similar muscle biopsies were obtained at the same time intervals for the non-massaged group.

The author’s advocacy of massage therapy includes this perspective:

“Complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) is increasingly used as a cost-effective adjunct to conventional medical care. Many CAM techniques, such as acupuncture, massage therapy, or chiropractic manipulations, are aimed at managing pain, relieving stress, and preventing injury.”

“The increasing use of massage therapy as an adjunct to conventional care for musculoskeletal injury recovery and the growing number of physician referrals for massage represent a shift toward nondrug-based therapies for personal health.”

“Given the spiraling cost of primary care and medications in the US, it is likely that more patients will seek out this therapy as well as other nontraditional medical alternatives to complement more conventional approaches to their healthcare.”

The authors define massage therapy as “physical manipulation of muscle and connective tissue at a site of injury, inflexibility, or soreness to reduce pain and promote recovery.” They hypothesize that massage therapy moderates inflammation, improves blood flow, and reduces tissue stiffness, resulting in diminished pain. They state that massage could be useful to a broad spectrum of individuals including the elderly, those suffering from musculoskeletal injuries, and patients with chronic inflammatory conditions, citing evidence that massage therapy reduces chronic pain and improves range of motion in clinical trials.

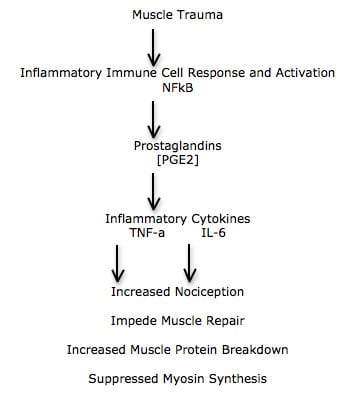

Acute muscle trauma results in inflammation and immune cell activation. The activated immune system produces and releases inflammatory proteins called cytokines. This inflammatory immune response is led by the cytokine nuclear factor kappa B (NFkB). NFkB impairs tissue healing. Consequently, any therapy which reduces NFkB accumulation would improve tissue repair.

The NFkB pathway also increases inflammatory prostaglandin synthesis [like prostaglandin E2 {PGE2}] and increases expression of other inflammatory cytokines [like interleukin-6 {IL-6} and tumor necrosis factor-alpha {TNF-a}]. These inflammatory cytokines further impede muscle repair by increasing muscle protein breakdown and suppressing myosin synthesis.

Of course, all of these inflammatory cytokines also activate nociceptors, causing increased sensitivity to pain (hyperalgesia). These authors propose that myotherapy/massage may disperse the accumulation of these inflammatory mediators, thus reducing pain afferentation. This is particularly useful in situations where areas of low blood flow, like the muscle tendon interface, restrict the access of circulating analgesic anti-inflammatory chemical compounds.

Additionally, a mechanical stimulus to a muscle will physically alter the cells membrane and the extracellular matrix and transmit signals via proteins known as integrins. Integrins in turn activate and propagate mechanotransduction signals that “modulate protein synthesis, glucose uptake, and immune cell recruitment.” The mechanical stretch during massage activates mechanotransduction signaling that increases muscle glucose uptake, protein synthesis and muscle growth. This would improve both the timing and quality of healing for injured muscles. “Any physiological benefits due to massage would likely be initiated through mechanical effects on skeletal muscle followed by changes to intracellular regulatory cascades.”

The mechanism of myotherapy/massage found in this biopsy study include:

- “Massage reduced signs of inflammation, and massaged muscles cells were better able to make new mitochondria—promoting faster recovery from exercise-induced muscle damage.”

- Massage activates mechanosensory sensors.

- Massage activates the formation of additional mitochondria, “presumably accelerating healing of the muscles.”

- Massage reduced accumulation of inflammatory mediator nuclear factor kappa B (NFkB), and reduced the activity of immune cytokines interleukin-6 (IL-6) and tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-a), “a sign of less cellular stress and inflammation.” This would mitigate cellular stress resulting from myofiber injury.

“In summary, when administered to skeletal muscle that has been acutely damaged through exercise, massage therapy appears to be clinically beneficial by reducing inflammation and promoting mitochondrial biogenesis.”

“These results elucidate the biological effects of massage in skeletal muscle and provide evidence that manipulative therapies may be justifiable in medical practice.”

Summary and Conclusions

Massage Does The Following:

- Activates the mechanotransduction signaling pathways

- Increases muscle glucose uptake, protein synthesis and muscle growth

- Increases the biosynthesis of mitochondria; this increases the production of the ATP energy required for protein synthesis and repair of injury.

- Reduces the production of NFkB.

- Reduces the production of inflammatory prostaglandins [PGE2].

- Reduces the production of inflammatory cytokines [TNF-a, IL-6].

- Reduces pain.

- Accelerates healing, faster recovery.

Chiropractors are well schooled in the concepts of tissue fibrosis, traumatically triggered inflammatory cytokines and prostaglandins, mitochondrial production of ATP energy, DNA activation with repair protein synthesis, inflammatory alteration of pain thresholds, mechanotransduction and mechanobiology as related to integrin influence on the genetic material, and how motion restriction opens the pain gate. Consequently, most chiropractors use myotherapy/massage therapy either directly (in office) or indirectly (as outside office referral) as an adjunct to spinal adjusting in clinical practice. Incorporation of formal myotherapy into our clinical practice helped us to achieve our clinical goals 25-33% quicker than without this addition.

References:

- Cyriax J; Textbook of Orthopaedic Medicine, Diagnosis of Soft Tissue Lesions, Bailliere Tindall, Volume 1, eighth edition, 1982.

- Cyriax J; Textbook of Orthopaedic Medicine, Treatment by Manipulation, Massage, and Injection; Bailliere Tindall, Volume 2, tenth edition, 1982. (2)

- Cyriax J and Cyriax P, Illustrated Manual of Orthopaedic Medicine, Butterworths, 1983.

- Roy, Steven; Irvin, Richard; Sports Medicine: Prevention, Evaluation, Management, and Rehabilitation; Prentice-Hall, 1983.

- Cohen, I. Kelman; Diegelmann, Robert F; Lindbald, William J; Wound Healing, Biochemical & Clinical Aspects; WB Saunders, 1992.

- Boyd, William, Pathology, Lea and Febiger, 1952.

- Guyton, Arthur, Textbook of Medical Physiology, Saunders, 1986.

- Robbins Pathologic Basis of Disease, “Inflammation and Repair,” Chapter 2, 4th edition, p 39.

- Manjo G, Joris I; Cells, Tissues, and Disease: Principles of General Pathology; Second Edition; Oxford University Press; 2004.

- Melham TJ, Sevier TL, Malnofski MJ, Wilson JK, Helfst RK, Chronic ankle pain and fibrosis successfully treated with a new noninvasive augmented soft tissue mobilization technique (ASTM); Medicine Science Sports Exercise, June 1998; 30(3): 801-4.

- Crane JD, Ogborn DI, Cupido C, Melov S, Hubbard A, Bourgeois JM, Tarnopolsky MA; Massage Therapy Attenuates Inflammatory Signaling After Exercise-Induced Muscle Damage; Science Translational Medicine; February 1, 2012; Vol. 4, No. 119; [epub].